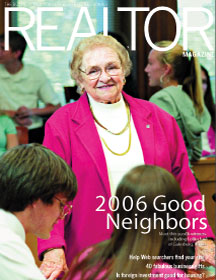

But Lolita Junk cared.

Junk is a 45-year real estate veteran and broker with Diversified Real Estate Services/GMAC. She had read in an American Legion Auxiliary publication about an alternative to the juvenile justice system, and in 1994 she set out to bring the idea—known as teen court—to her community. She recalls that her son’s girlfriend at the time supervised a detention center and told her that by the time kids reach detention, “it’s too late.”

After hundreds of phone calls, and meetings with 26 different agencies, Knox County Teen Court was open for business. The program offers a second chance to first-time, nonviolent offenders between the ages of 11 and 18. Teens acknowledge their guilt and stand trial before their peers. Local attorneys volunteer as judges, and teens volunteer as prosecutors, defense counselors, and jurors.

Burnett remembers his trial well. “I was looking at the jury, and they were kids I played sports with and saw in school, and now they knew everything about me, my family, my police record,” says Burnett. “I couldn’t hide what I’d done.”

The sentence—100 hours of community service with the Red Cross and a local senior home—became a turning point for the troubled boy. “Teen Court and Lolita helped me change my life,” he says.

Today about 12 teens per month appear before the Knox County Teen Court. Since the first trial in 1995, the program has helped more than 1,600 teens and served as a model for more than 100 teen courts in Illinois and many more around the country.

Junk, a mother of eight, says Teen Court’s power comes partly from the fact that defendants are held accountable and expected to make amends. In traditional courts, first-time offenders often get just a slap on the wrist, says Junk. “They don’t learn that actions have consequences. Early intervention gives kids a great opportunity to change their lives and make good choices.”

Sentences range from drug and alcohol counseling and anger management classes to community service. Juries can get very creative, ordering a teen to make a collage, perform good deeds, or write an apology letter to a victim.

“We had one teen who loved to aggravate an older neighbor. One Christmas, he destroyed several of her lawn ornaments. His sentence was to do five nice things for the neighbor. He helped her carry groceries and shoveled her snow. Now he and the neighbor are friends. In fact, she recently took him fishing,” says Junk.

To make Knox County Teen Court a reality, “Lolita did everything,” says Steve Watts, a local attorney and Teen Court judge who’s now president of the group’s board of directors. She recruited volunteers, made presentations at schools, and obtained community service opportunities and funding. In 2005, after years of advocacy work by Junk, a state law went into effect enabling Illinois counties to assess a $5 fee to fund teen court operations.

Junk’s commitment to Teen Court extends to the individuals who come before it. Junk interviews teen defendants and their parents to ensure they’re committed to the concept. And her involvement doesn’t stop when the sentence is handed down. She follows up with the teens to see how they’re faring.

Most succeed. The recidivism rate is about 8 percent, low compared with that of traditional courts, says Junk.

“After my community service, my grades slowly went back up,” says Burnett. “I graduated from high school, went into the service, and finished some college. Lolita and her husband [who passed away last year] became like grandparents.”